Agents in Legal: Solo Contributors or Integrated Teammates?

How we might design multi-agent systems for legal processes

I’ve spent a fair bit of time recently wondering whether to think of AI agents for legal work as solo contributors or teammates integrated into a process.

Most of today’s real, practical use cases involve agents as solo contributors: give an agent or assistant a discrete task, let it run, check the output, iterate. That’s a perfectly valid way to use them - and to be completely clear, it’s where almost all the use cases sit today. There are plenty of lower-hanging fruit than multi-agent systems. But let’s for a moment start thinking ahead.

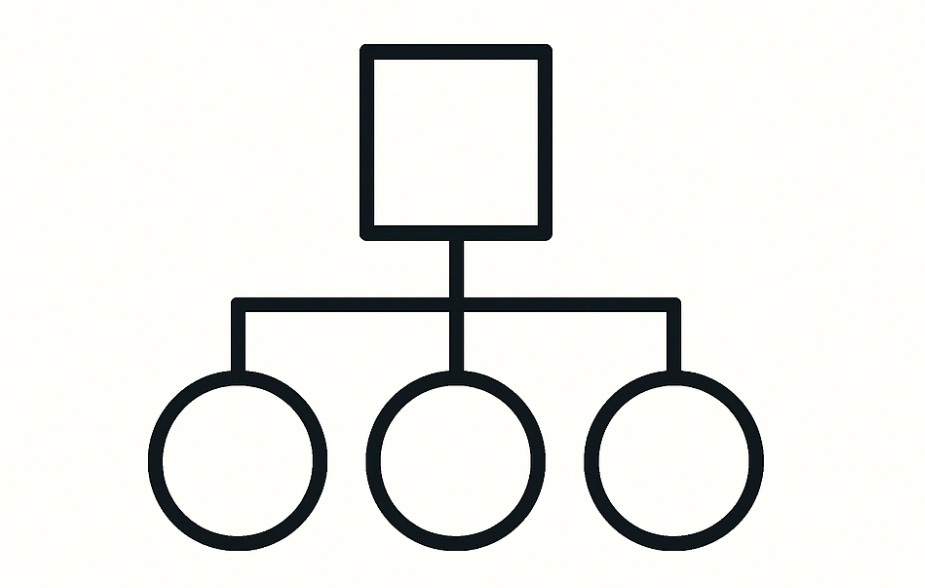

Lessons from coding systems

Other fields are moving towards multi-agent systems. One example is vibecoding tools like Replit and Lovable, which have enjoyed almost unprecedented ARR growth by building multi-agent systems that allow users to develop full-stack software applications.

Instead of pointing one agent at a coding task, they deploy a small coordinated team: a project-management agent breaks work down and keeps the user updated, specialist coding agents handle components, and an architect agent reviews and integrates the final output. A lot of the value comes not because each agent is smart (a lot of this is a relatively thin wrapper on top of LLMs, usually Claude), but from the structure and orchestration around the agent system.

A Replit project management agent calls “the architect” to review its work

Legal work hasn’t really made that shift yet. Most legal uses today are reactive, serving each attorney’s one-off request: summarise this document, extract these facts, draft this clause. There is enormous value in these use cases – we could spend the next few years focused on these and we would barely scratch the surface - but isn’t there a bigger opportunity here?

Types of multi-agent systems

If you’re going to follow one person on agentic systems, follow Dazza Greenwood. Seriously, he built his first agent in the late 1980s! He knows more than almost anyone on the topic and yet still manages to present it in an easily digestible way.

I recently found myself reading Dazza’s excellent article on agent design patterns – an accessible framework for designing interactions between agents – and wondering how each pattern may or may not fit into legal work. So, with full credit to Dazza on the definition of each agent design pattern, I have layered on top my thinking about the pros and cons of each for legal matters.

Sequential Pattern

What the pattern is

A fixed, ordered pipeline: Agent A → Agent B → Agent C. Each performs its step, then hands off. The sequence is predefined.

How it maps to legal work

An example for legal teams might be: gather requirements → draft → review → finalise

For instance, an agent extracts the requirements from an intake form, another drafts a document based on those requirements, a third performs a structured QA review before human approval.

How it might be applied

• Break the matter or workstream into explicit stages with readiness criteria.

• Use agents for well-defined tasks inside each stage.

• Enforce human review between major phases.

• Don’t trigger the next phase until the last one meets its standard.

Pros

• Predictable, auditable and easy to monitor.

• Ideal for standardised, high-volume matters.

• Reduces ambiguity around who does what and when.

Cons

• Inflexible. One error might block the pipeline.

• Poor for matters requiring iteration or backtracking.

• Can feel rigid as real-world facts evolve.

Hierarchical Pattern

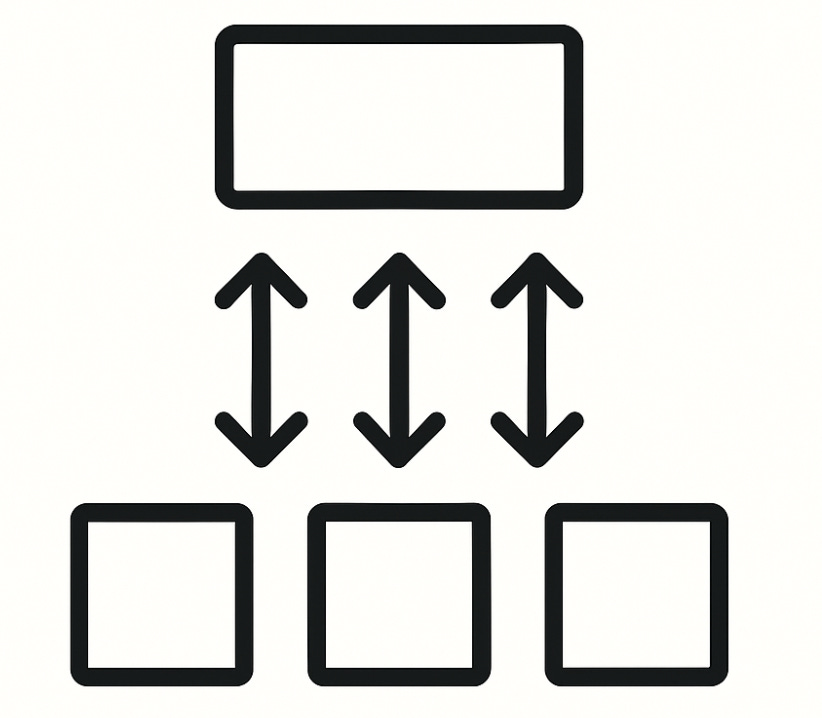

What the pattern is

A master–worker model. One agent (the “supervisor”) breaks the work into subtasks and delegates them to worker agents.

How it maps to legal work

Partners set direction → associates break down the tasks → specialists and paralegals execute clearly defined components.

How it might be applied

• Use a planning agent to define the matter plan.

• Assign specialist agents narrow, scoped subtasks (clause drafting, research extraction, chronology building).

• Route ambiguous or missing information directly to humans - not to other agents.

• Treat each delegation like a brief with acceptance criteria.

Pros

• Handles complexity well.

• Enables parallel execution.

• Makes responsibility explicit.

Cons

• Hard to automate good task decomposition.

• Coordination overhead increases with system complexity.

• Mis-scoped tasks propagate downstream errors.

Collaborative Pattern

What the pattern is

Agents work more like peers toward a shared goal. They may contribute to a shared workspace or update a shared state, coordinating without a central arbitrator.

How it maps to legal work

This mirrors an ideal view of multi-disciplinary collaboration: tax reviewers, privacy reviewers, commercial lawyers and local counsel all contributing to a shared document or matter. That said, it is rare in the real world to have such a truly collaborative approach - more often than not, one firm or team acts as quarterback to drive a process.

How it might be applied

• Create a shared workspace for matter contributions.

• Allow multiple agents to propose edits, analyses or suggestions.

• Preserve attribution so humans know which agent proposed what.

• Use collaboration when you need diverse viewpoints, not strict control.

Pros

• Reflects ideal vision of multi-disciplinary collaboration.

• Surfaces diverse expertise simultaneously.

• Works well when specialists need to contribute in parallel.

Cons

• Can become noisy without constraints.

• Hard to maintain coherence without oversight.

• Conflicting contributions can accumulate.

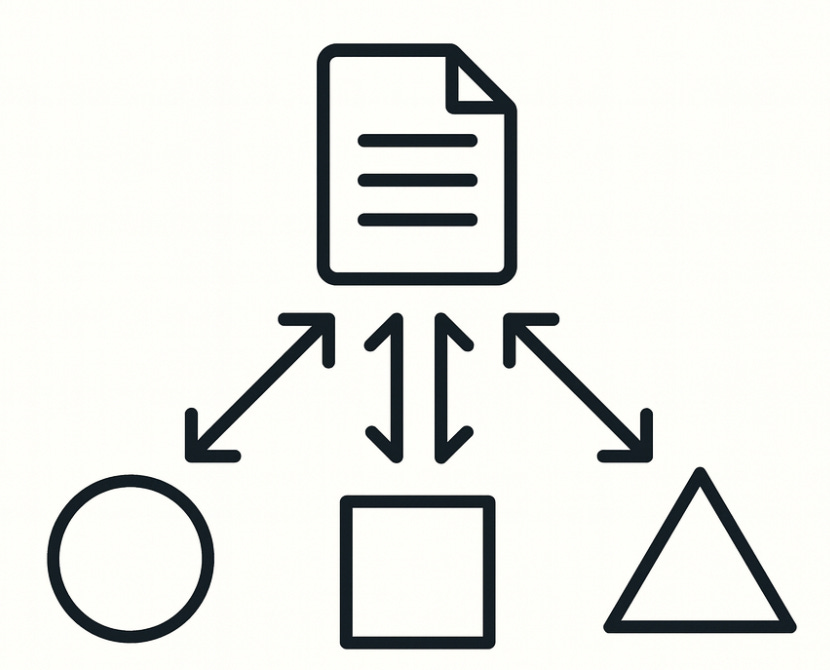

Mediated Pattern

What the pattern is

A mediator agent sits in the middle, receiving inputs from other agents, integrating them, and deciding what to pass forward or reject.

How it maps to legal work

Think of the matter partner or senior associate in Corporate who coordinates a multi-department due diligence effort - receiving drafts, comments and analysis from multiple contributors, then synthesises them into a unified document or plan.

How it might be applied

• Deploy specialist review agents, but have all outputs go through a mediator.

• Use the mediator to merge changes, resolve conflicts, apply style and structure.

• Control quality centrally via the mediator rather than peer-to-peer editing.

• This approach suits documents where a single authoritative voice is required.

Pros

• Produces more coherent outputs.

• Reduces conflict between agents.

• Supports strong governance and version control.

Cons

• Mediator becomes a bottleneck.

• Reduces diversity of perspectives if overly strict.

• Requires strong design of the mediator logic.

Hybrid Patterns

What the pattern is

A combination of patterns. You might use sequential flow for the backbone, hierarchical delegation for complex pieces, and mediated interactions for key decision points.

How it maps to legal work

Legal matters rarely follow one clean pattern. Facts change, stakeholders intervene, tasks run in parallel, regulatory updates appear. Hybrid patterns capture this complexity.

How it might be applied

• Start with a core workflow (intake → requirements → draft → review).

• Add hierarchical decomposition for multi-step tasks.

• Use collaborative agents for specialist input.

• Insert a mediator agent for integration and finalisation.

• Let the orchestration layer route tasks dynamically.

Pros

• Handles complexity, exceptions and branching.

• Allows flexible orchestration around a structured core.

Cons

• Hard to design, test and maintain.

• Requires robust error-handling and state tracking.

Why multiple agents? Why not just one agent prompted to follow multiple steps?

One agent has one chain of thought, one objective at a time, and few mechanisms for separating roles like planning, execution, review, or critique. Multi-agent systems introduce specialization and division of labour: one agent plans, another executes, another reviews, another integrates. This mirrors how real work gets done. It also creates fault-tolerance - if one agent produces weak output, another can catch it. Most importantly, multi-agent systems allow workflows to scale. A single agent forced to plan, execute, evaluate and revise its own work collapses into a monolith that becomes brittle and unpredictable as complexity increases. Multiple agents, each with a narrow, well-defined role, behave more reliably and map more naturally onto the structure of real legal matters.

Conclusions: Integrated teammates or isolated tools?

The single-agent, single-task model isn’t wrong. It’s where we get almost all the reliable value today, and I do not mean to dismiss those use cases as outdated or get too far ahead of where we are today. As always, there are plenty of easier wins.

But that doesn’t mean we can’t start exploring the next level - the harder wins with the potential for more transformational impact. In my opinion, the long-term direction is toward multi-agent systems acting as coordinated teammates inside a structured legal workflow, similar to what’s emerging in coding.

The shift won’t happen instantly. But over time, applying these patterns could move agents from isolated task-doers to something closer to integrated members of the team. And that is when we may start to see agents more actively involved in delivering outcomes, rather than simply discrete task outputs.

Inference and memory requirements of an agentic system present the opportunity to build useable agentic law teams; this will require engineering skills that are old world DB management, cloud, and the new world of LLM inference, memory, and management in context, to name a few

big ticket issues.